Ferries

In 1792 Scarinish was recoded as having a harbour in need of considerable improvements. At that time there was a regular ferry boat sailing between Coll and Tiree, and between Coll and Mull, "but there is no stated ferry between Tiree and Mull, although there is a great need."

Even by 1845 it was reported that there has been no ferry to Tiree for some years. “Our means of communication are accordingly extremely irregular and uncertain, depending on any casual conveyance that may occur."

The Dunara Castle was the first steamer to make regular trips to Tiree in 1875, sailing weekly from the Broomielaw on the Clyde to most of the Hebridean islands for the Orme Company. The Hebrides, built in 1898 for the McCallum Line, sailed a similar route.

The completion of the railway to Oban in 1880 opened up the west coast and in 1886 the Highland Fisheries Company began sailings with the Trojan from Oban to Tiree and Barra three times a week, a dramatic improvement. In 1889 this route was taken over by David MacBrayne using the Clydesdale.

However, no worthwhile pier had been built on the island, and steamers had to lay off Scarinish. The biography of Lady Victoria Campbell, who frequently travelled to Tiree between 1886 and 1909, paints the following picture: "The steamer always ‘passes’, but there are many mornings when the mails and the passengers in the cargo-boat cannot go out to her, and this may happen for a week or ten days in succession.

Very often it turns on the number of young men present, and willing to take a hand, and with two or more men at each oar, they assist the agent of MacBrayne to get the boat out of the narrow straits of Scarinish Harbour to the steamer." The Reading Room in Scarinish (now An Iodhlann) was built for passengers waiting to board.

After years of political pressure, the Gott Bay pier was completed in 1914 by G. Wolfe Brennan of Oban. It was extended in the 1950s. Originally a railway ran down the centre of the pier with a bogey pulled by horse. During the First World War, Tiree had a weekly boat from Oban, the Plover, which was attacked by a German submarine in the Sound of Gunna with no loss of life.

After the war the Cygnet, a small and uncomfortable boat, was put on the Obanto Tiree run. One passenger wrote "… to have one’s feet hanging in mid-air, and one’s back supported or forced forward, are serious aggravations of the wet and cold, the driving wind, the pitching deck, with the sight of the misery of one’s fellow-travellers, in an unventilated, evil-smelling saloon, for sole alternative." Alasdair Sinclair, Brock, remembers "there was nowhere at all to sit on the Cygnet. You just stood on deck, ankle deep in water, and watched your luggage floating about."

David MacBrayne’s company was in financial difficulties and there was widespread dissatisfaction with the service. In 1928 the company was restructured with a promise to deliver new boats and in 1930 the Lochearn was delivered for the Tiree run. The Cygnet was scrapped. The new vessel had much more comfortable accommodation but managed only nine knots. She continued on the run until 1948.

The building of an RAF base on Tiree in the Second World War meant an increase in traffic to the island and MacBrayne’s chartered the Hebrides from MacCallum Orme to serve the Oban-Coll-Tiree route.

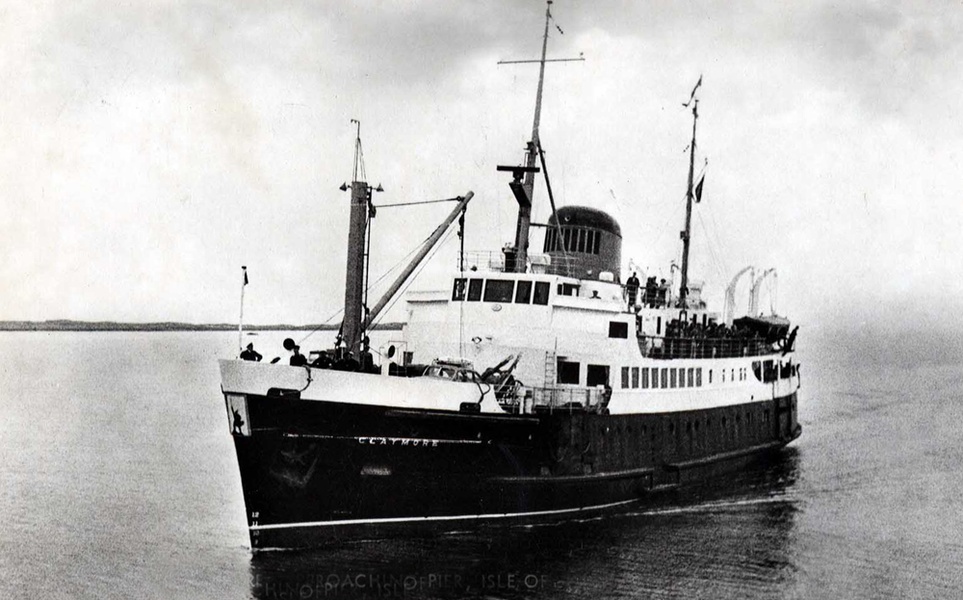

In 1955 the second Claymore began serving the island from Oban. Well fitted-out, she was the last MacBrayne boat to have first and second class. She had no side ramp and animals and cars had to be winched ashore.

In 1973 David MacBrayne and the Caledonian Steam Packet Company merged to form Caledonian MacBrayne. Within weeks the new company’s services to Tiree were badly disrupted when the Loch Seaforth, which had just come down from Stornoway, struck a rock in the Sound of Gunna. Passengers and crew abandoned ship with no injury, and the stricken vessel was towed to the Gott Bay pier. She sank soon after, leaving the pier blocked for two months until she was salvaged by a Dutch floating crane.

The third Claymore was launched in 1978. She was fitted with a side and stern ramp, and was capable of 15 knots. The Lord of the Isles was launched in 1989 and was the first vessel to use the new linkspan pier in 1992. The Clansman, launched in 1998, is the latest ferry to serve the route.

Fishing

Shell fish, mainly maorach (limpet) and faochag (wilk) have been eaten in large quantities since the first settlers came to Tiree. The remains of a fish trap of uncertain age can be seen in Heanish between Dùn Hianais and Eilean nan Gobhar (the Island of Goats).

More recently, fishing from the shore was done with a slat-chuilc (bamboo rod). Cnotagan (hollows where limpets, dog whelks or potatoes were ground) can be seen at numerous carraigean (fishing rocks). This bait was thrown into the water immediately before fishing.

In 1786 the British Society for Extending the Fisheries sent John Knox (no relation of the religious leader) to the Highlands to look for new fishing grounds and harbours. When he came to Tiree he found the islanders "depend chiefly on the produce of the ground, though the coasts abound on every side with all the varieties of… fish.”

In 1792 it is reported that in "the summer of 1787 there were several companies of natives employed, and though of little experience, they caught at one letting of 200 - 300 hooks, from 30 - 80 cod and ling... and those who had harpoon and line caught at the same time sail-fish [basking sharks]... there are yearly companies from Barra…having more experience are more successful than our own men. There have been also adventurers from Ireland and the east of Scotland successful. In one sloop particularly…they seemed to have caught in two months from 12,000 to 16,000 cod and ling…They do not in this district, pursue fishing with spirit."

By 1845 little had changed. In this year it was recorded that fishing "does not appear to have been hitherto prosecuted with the activity and perseverance which it deserves... though almost all are occasional fishers, yet few follow it steadily as a profession. Out of 94 fishing skiffs only 10 are regularly employed." The writer goes on to lament the presence of fishermen from Aberdeenshire with more powerful boats beside which "the native boats are but slight cockle-shells."

The lack of a suitable harbour was addressed in 1847 when new piers were built in Port Bhiostadh at the Green, Port Driseag in West Hynish, Port an Tobair in Balemartine, at Milton and at Port a’ Mhuilinn in Baugh. The remains of these piers can still be seen.

Fishing has always been a dangerous occupation but Fuadach Bhail’ a’ Phuill, the Balephuil Fishing Disaster in 1856, had a devastating effect on the west end of the island. The July morning had dawned calm and sunny. Only an arc of a rainbow in the west warned Archibald Campbell (Am Bòidheach) from Barrapol not to go to sea. But seven boats did set out from West Hynish for the Skerryvore fishing banks. At midday a sudden storm scattered the fleet and nine men were drowned. One boat, with the dead skipper Donald MacLean (Dòmhnall Ceann na Creige) still at the helm, came ashore on Coll. Another two boats were driven to Islay where the crew were looked after by a woman whose uncle had been a factor on Tiree and had himself lived in West Hynish.

In 1860 the estate purchased a forty foot fishing boat, the Duchess, for the use of Tiree fishermen. The factor, John Campbell, reporting to the Duke in 1862, wrote "the crew of the Duchess have had very good fishing... and brought in 300 fine line fish." They kept their sails in the Scarinish store until they were accused of stealing some sail cloth from the storekeeper, Mr. MacQuarrie. Unfortunately the Duchess was wrecked in Hynish Bay in 1871.

The Green, so called because it was used to dry fish, was a favourite spot of the east coast fishermen who continued to come every summer. It is said that the Duke employed several east coast families, among them Downies, to show Tiree fishermen the arts of line fishing.

For four seasons between 1914 and 1918, and for two years in the 1930s, there was a herring boom on Tiree and anyone who had a boat was busy. One Balephuil crofter told how he earned £35, a large sum at the time, in one week as a crew member of a herring boat. Gott pier was busy with clann-nighean an sgadain (herring girls) who gutted and salted the fish. At least two married locally in Scarinish.

A small number of boats currently fish out of Milton and Scarinish, predominantly for velvet crab with some lobster, crayfish and brown crab.

Brown trout were introduced by the estate into Loch Bhasapol after 1845 and have thrived. A similar attempt by Alf Bruton in the 1950s at Loch Ghrianail in Kirkapol was not successful.

Sailors

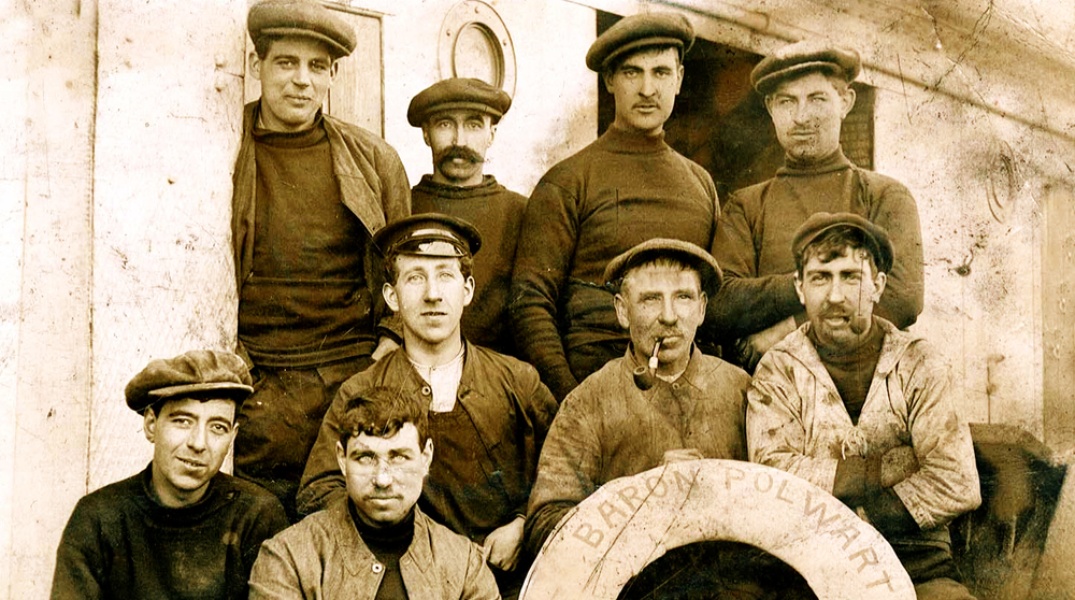

Tiree men have long been associated with the sea. In the early nineteenth century men began going away on deep sea sailing ships and when steam ships began to multiply in the second half of the nineteenth century even more men from Tiree went to sea.

Tiree was also well-known for its smacks and schooners, which carried cargo around the west coast. There were over thirty in the 1880s. The most famous one was the Mary Stewart, sailed by Donald MacLean (Dòmhnall Òg). Her remains lie in Scarinish harbour today.

Tiree has produced many fine sailors. One of the finest was Donald MacKinnon who won the most famous tea clipper race of all time in 1866.

Donald MacKinnon (Dòmhnall ’ic Nèill ’ic Dhòmnaill Ruaidh) had three brothers who also became sea captains and the fourth a doctor in the Belgian court. Donald made his name on the Canada run, breaking the record for the voyage from Quebec to Greenock.

At that time London tea importers paid a premium for the first China tea of the season to arrive in London. Consequently a fleet of fast tea clippers was built and lined up each year for the dash home to London.

On May 30th 1866 16 clippers were ready at the Pagoda Anchorage, Foo Chow Foo. The Fiery Cross was away first, followed by the Ariel, the favourite, and two hours later the Taeping, captained by Donald MacKinnon and loaded with 1,108,709 pounds of tea.

Donald MacKinnon’s boat, The Taeping, arrived at London’s East India Dock half an hour ahead of its nearest rival, 16,000 miles and 99 days after leaving China.

After the race Captain MacKinnon returned to Tiree in glory and was given Pairc a’ Chrannaig (park of the pulpit) in Heanish. However his trip home was to end in tragedy. The ferry from Mull, the Chieftain’s Bride, encountered vicious weather, and the crew begged their famous passenger to take command. To lighten ship he ordered 54 head of cattle and sheep be thrown overboard but in the battle to save the ship he was injured.

He seemed to recover and rejoined the Taeping in London for her return journey to China. Tragically his injuries were more serious than he thought. He became ill again on the voyage round the Cape and was put ashore at Algoa Bay. Picked up by a later ship, he died and was buried either at sea or near Cape Town.

Skerryvore Lightouse

Robert Louis Stevenson called it "the noblest of all extant deep sea lights." Skerryvore light is not only an engineering wonder - 138 feet tall and 58,000 cubic feet of granite erected on a tiny rock surrounded by boiling breakers - but a tower of unsurpassed grace and beauty.

An Sgeir Mhòr (the large skerry) lies 11 miles south west of Tiree. It is one of a line of reefs which claimed over 30 ships between 1790 and 1840 at a time when the Clyde was lined by the busiest ports of the British Empire.

Alan Stevenson, the 27 year old son of the chief engineer to the Northern Lighthouse Board, was appointed in 1834 to build the lighthouse. He soon realised that only a solid stone structure could withstand the might of the waves when the hardness of the underlying rock (Lewisian gneiss) would not allow foundations. The lowest 26 feet would be entirely solid and the whole structure would weigh 4,308 tons, four times heavier than the Eddystone light.

Work began in 1837 building a dock, workshops and lodgings at Hynish. Grey, locally quarried gneiss was used at first, but work was slow and quarrying was switched to Camas Tuath on the Ross of Mull where the pink granite was easier to shape. The different stone colours can be seen in the buildings around Hynish.

The next year, a six-legged wooden barracks that could sleep 40 men was built in Gourock and assembled on the rock. Twenty one men worked 16 hours a day for five weeks to secure it but their work was in vain as a storm the following winter swept it away.

In 1839 a second, stronger wooden tower, 60 feet tall, was erected on the site and the rock surface was levelled off. No fewer than 296 dynamite charges were needed to remove 2,000 tons of rock, leaving

"in the midst of this torn and fissured surface, a magnificent circular floor, 42 feet in diameter, as smooth as a billiard table. On this floor the whole weight of the tower was intended to rest."

In Hynish 80 stonemasons worked throughout the winter precisely shaping over 4,300 blocks using wooden templates and setting them in place on a circular platform. This allowed them to be set in place on the rock with little adjustment.

Life on the rock was even harder. Rough seas could prevent supplies arriving for seven weeks at a time and occasionally food and fuel were in short supply and tobacco ran out. "Our slumbers, too were at times fearfully interrupted by the sudden pounding of the sea over the roof, the rocking of the house on its pillars and the spurting of water through the seams in the doors", wrote Alan Stevenson in his diary.

In July 1842 the final stone was added to the 97th course. So accurate had been the drawings that the final tower was only one inch taller than expected. Equally impressive was the fact that no-one had lost their life in the five seasons of construction. The whole enterprise had cost £86,977 17s 7d.

The Hynish pier was extended in 1843 to allow the lighthouse vessel to berth. The dock has a tendency to fill up with sand and an ingenious flushing system designed by Stevenson using water from a reservoir up the hill and wooden gates, was used to try to keep it open.

Inside the lighthouse, arrangements were standard: two engine rooms at the bottom, then a workshop, living room, store room, lower and upper bedrooms, fog signal room and at the top a control room.

Three lighthousemen served at a time, working a rota of six weeks on and two weeks off which they spent at their quarters in the Upper Square. They were later transferred to Earraid, near Iona. Communication with Tiree was by a sequence of balls hung out from the lighthouse and monitored by the signalling tower in Hynish.

In winter storms lashed the waves 60 feet up the tower and one young keeper, Soutar, is said to have hanged himself in a cave at Hynish in fear of returning to the rock.

In 1954 a fire gutted the lighthouse requiring a lightship to be anchored nearby until repairs could be effected. In 1994 Skerryvore lighthouse was automated.

The Hynish complex has recently been renovated by the Hebridean Trust.